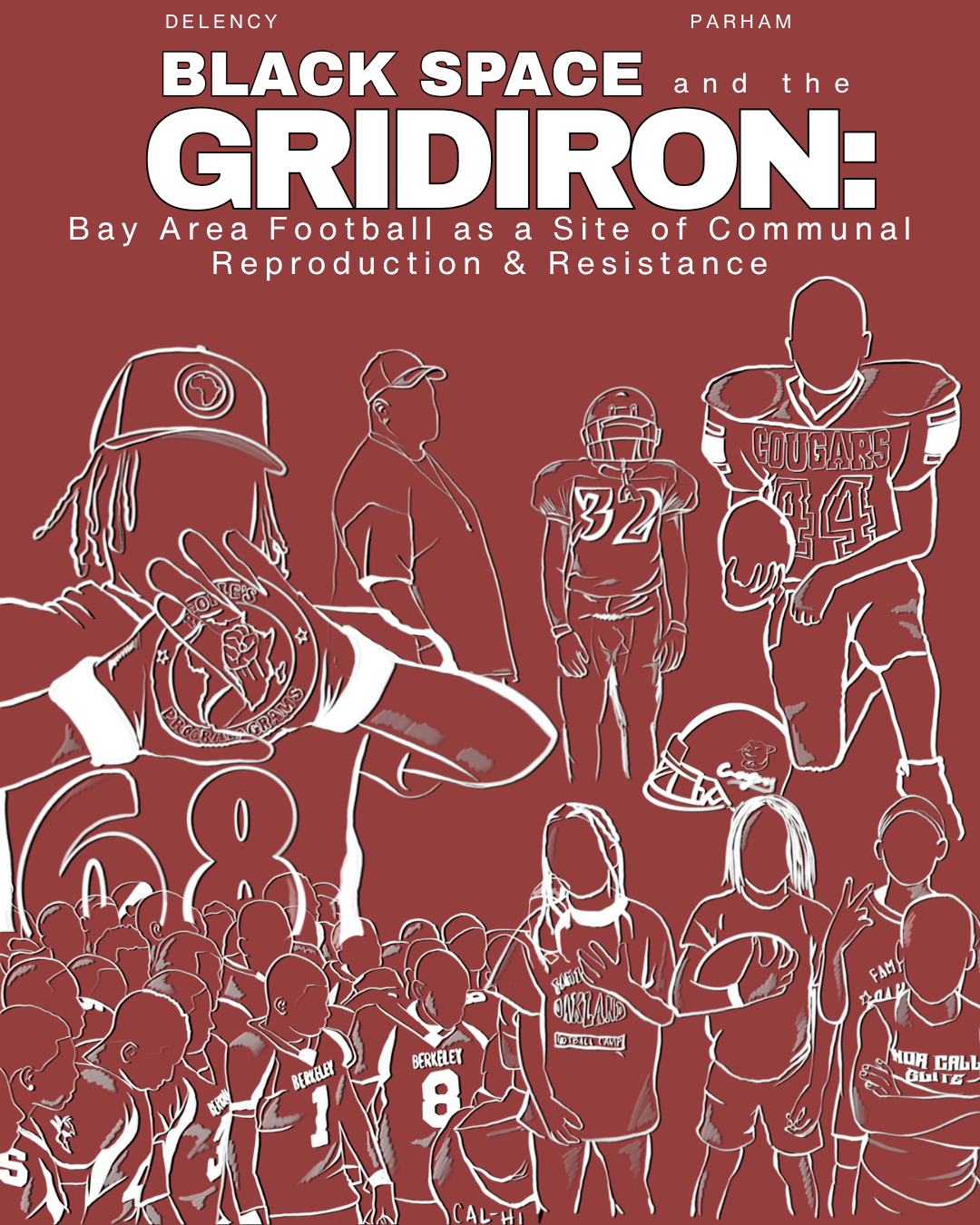

Art by Dariane Beamon

Written by Delency Parham

Preface

This essay examines the role of youth and high school football in the Bay Area as a contemporary site of Black communalism, cultural continuity, and self-determination. Amid the displacement caused by gentrification and the erosion of historically Black institutions, these football programs continue to serve as vital spaces for connection, mentorship, and grassroots organizing. Drawing from personal experience as both participant and organizer, the essay situates Bay Area youth football within a lineage of community-driven institutions that have long operated independently of state structures. Programs such as the Oakland Dynamites, Richmond Steelers, and 510 Legacy exemplify the enduring ethos of collective effort and mutual support within Black communities, providing a foundation not only for athletic development but also for social cohesion and political education.

Through the work of People’s Programs—a community organization partnering with local teams to offer free health services, sponsorships, and academic support—the essay illustrates how existing community infrastructures can be mobilized for broader liberation work. Rather than imposing new frameworks, it argues that contemporary organizers should recognize and materially support these longstanding sites of Black life as bases for positive change.

An Intentional Grounding

As youth and high school football seasons come to a close, I find myself once again inspired by the work and achievements of so many New Afrikan (Black) players, coaches, parents, and programs around the Bay Area. Not only have they worked hard, competed at a high level, and made a ton of great plays along the way, but most importantly, they’ve created spaces for Black people to come together and connect on a weekly basis. The value that these Black spaces have historically brought to our people cannot be understated. Whether it’s that one house in the family where we all link up after school or on holidays, that one club in the city that all our parents used to hit, or during slavery when our ancestors would gather in the woods and plot plans of escape, spaces forged and developed by/devoted to Black folks have been part and parcel of our ability to relate to and develop alongside each other—in other words, these spaces are the foundation by which Black people organize themselves.

Although the 21st-century commodification of the organizer has led to a focus on the hypervisible and celebrity activists among us, the humble grassroots have long put in work to make the youth football ecosystem in Oakland, Richmond, Berkeley, San Francisco, and the broader East Bay a place of refuge and communion for its Black inhabitants. As a kid, I myself played for programs like The Berkeley Cougars, Albany Bobcats, and Berkeley High Football, and it is within these milieus that the ethos and practices I carry today (love for and belief in New Afrikans) were incubated. Decades later, against a backdrop of severe deprivation and marginalization, this Black Bay Area football scene is still pouring into my love and respect for my people.

It’s no secret that gentrification has ravaged the East Bay, forcing many poor and working-poor Black people to migrate hours away, or even sometimes out of state. A natural effect of this politically engineered circumstance is the erosion of core institutions — neighborhoods, community centers, free programs — that were central to our development as they served as locales for us to build with and relate to one another. This reality has created a vacuum, and for the New Afrikans that remain in the Bay Area, we are wondering what we can do, and where we can go, to get that old thing back. I argue that much of what Black Bayarians are looking for, exists in our youth and high school football scenes.

For some reason, I feel compelled to state the fact that this sect is not perfect. Like all things, it comes with contradictions. I know in recent years there have been some situations that have resulted in an increased police presence at games and events (for the sake of time, I’ll need to revisit this in another writing), but what I’m putting forth right now is that this arena, being one of the longest-standing hubs for Black people in the Bay to come together, by default, serves as a base for redeveloping and reorganizing Black people in the Bay for our collective well-being (socioeconomic, political, and cultural). A quick look at history will show us how and why.

Photo by Andre Malik

A Proven Framework

The institution of youth football in the Bay Area goes back as far as the 1960s with the establishing of programs such as the Oakland Dynamites and the Richmond Steelers. To try and quantify the amount of families these two legacy organizations have positively impacted would be an exercise in futility. What makes their work so legendary (in my humble opinion) is the fact that much of it has been done while functioning outside of local and state government institutionalization. In other words, these organizations are completely operated and developed by the community—making them grassroots programs in every sense of the word. This lack of state backing, however, has not prevented them from supporting Black people in their towns for nearly 60 years—no matter what obstacles have been presented. For example, in the 1970s, the Steelers lost their city charter and were forced to practice and play in Crockett, a small town about 20 minutes away from Richmond. Where most would have canceled the season, the Steelers organized a busing system to get players back and forth to games and practice. Parents and coaches wouldn’t let bureaucracy stop them from serving Black families. In present day, that ethos of determination and collective support can be seen when the Dynamites or East Bay Warriors qualify for national championships in Florida, and the community rallies to donate money to ensure they can afford that trip.

When it comes to high school football, the Bay has produced a number of standout New Afrikan players. Many have gone on to earn full-ride scholarships and have success on the collegiate level—with some going on to play in the NFL. And for those that aren’t able to go on and play professionally, they often return to the Bay and find success in other fields (academia, entertainment, and entrepreneurship). A common thread amongst these players is to return home and contribute to their communities in any ways they can. Whether it’s starting teams, doing holiday giveaways, or running youth programs, they aim to provide for the community and people that once provided for them.

What I’m trying to bring into focus is that football for Black people in the Bay Area has always been more than just a game. Despite the benefits of the sport often being reduced to the opportunities of discipline, violence prevention, and brotherhood for Black boys, the truth is, for the many Black Bayarians that have immersed themselves into the space, it has been a conduit for our communal philosophy and practices to materialize. These teams and programs are core institutions by which much life, opportunity, and relationships have been forged. And where these programs will really make a leap is when organizations that claim to be dedicated to Black people begin to support them in material ways. This is what we at People’s Programs have strived to do for the past three years.

In my analysis, where many communal political organizations fall short is when they believe that their frameworks and methods are the only correct ones. This parochial (narrow) mindset often results in a failure on our part to recognize the positive forces and real work that is already being done within the community. While the fact is political organizations will need to start and develop their own programs, it is also true that they can save themselves a lot of time by supporting those which the people in their locales have already developed. For People’s Programs, that meant partnering with teams and people within the youth and high school football sector here in the East Bay.

People’s Programs in the Field

Our first effort came in 2023 when we took our free mobile health clinic to Oakland Technical High School to provide free physicals at the Fam First annual camp (a free camp put together by NFL vets Marshawn Lynch, Josh Johnson, and Marcus Peters). Later that same year, we partnered with Daniel Harper, who at the time was a two-sport athlete (Football & Track) at El Cerrito High School, and his brand D1, on an exclusive pair of football gloves. The creation of the gloves culminated in a video and photoshoot featuring top youth and high school football players from around the Bay Area. I’m proud to say that many of the high school players involved in the shoot are ballin’ on the D-I level as I type.

Each year has seen us expand our work and deepen our relationships with these players and coaches. In 2024, we not only took our mobile clinic back to the Fam First camp, but we also pulled up to the Berkeley Junior Jackets and 510 Legacy registration days to give their players free physicals as well. Our collaboration with 510 Legacy, a youth football team out of West Oakland, ended up expanding past just the physicals. We were able to come on as a sponsor for the season, securing them new bags for players to carry their equipment in (when I played for the Berkeley Cougars, It’s All Good Bakery sponsored our bags), and also working with Roderick’s BBQ to get free meals for all Legacy players for their last home game of the regular season.

2025 brought even more partnerships and collaborations. We worked with Marcus and his Village 7-on-7 team to put on a tournament in May, and partnered with a local restaurant, Touch of Soul, to provide free meals to all the players and coaches in attendance. A few months later in July, we organized medical professionals to work two camps and two team registration days, bringing free on-location physicals to over 200 athletes. In August, we organized Oakland firefighters and medics to work the Oakland Dynamites Legends in the Making tournament (two of the firefighters were my Pop Warner and high school football teammates, and another played football at Skyline High School in East Oakland. Shoutout Craig, Lee May, and Jeremy!). What I’m most proud of, though, is the free pregame meals and tutoring sessions we gave to players from 510 Legacy on Saturdays in September.

“I look at the positive attributes of my people, not the negative attributes of my people. Thus, every day I say, ‘Black people are beautiful! Black people are strong! Black people are intelligent! Black people are coming together!’ And I say it every day, 24 hours a day, to the people every time I see them. By doing this, I’m hoping to transform the atmosphere in my community.” —Kwame Ture

The picture I’m trying to paint here is one of reciprocity, the power that resides within the people, and how we have, and will, continue to come together to get things done. You help people, and they’ll help you! Last weekend, we did the photoshoot for our newest pair of gloves at McClymonds High School (Mack) in West Oakland, and I couldn’t help but get an overwhelming sense of pride for my people. Just seeing all these Black folks coming together to create, commune, and watch us all rally around the youth—it’s hard to put into words that wave of emotions and spirit that one gets in these moments and settings. Perhaps it’s the intergenerational element of it all? In attendance were people I grew up playing with and against—their kids, my little cousins, friends of my mother. My childhood homegirl Nini even brought her son out on the way to his championship game! We had families driving out from Brentwood. Players from Richmond, San Francisco, Concord, Berkeley… we had top recruits in the nation born and bred out here in the Bay Area, telling the next generation how they too can make it to the next level. Then you look out into the parking lot right next to the field, and there goes the People’s Programs mobile clinic (after our windows got busted a few times, Marcus and his father, Michael, a legendary football coach at Mack, said we can park it there and they’ll keep it safe). It was an experience that filled my spirit and further deepened my appreciation for my people.

2 Minute Warning

This current landscape in the Bay Area for Black folks is very reminiscent of the 20th-century first and second Great Migrations, which brought our ancestors here in flux from the South. Just like them, we suffer from economic instability and a lack of institutional infrastructure, and racism and classism are at the bedrock of our everyday experiences. In reading books and talking with elders, what I’ve come to learn is that our people only made it through that period by building communal networks which allowed them to ensure the safety and welfare of one another. Whether it was helping people find and keep housing, taking donations for food and clothes, or starting programs for creativity and learning—whatever it took, that’s what we did. And as local and state governments continue to show us—the people, especially poor and working-poor Black people—that our economic, social, and political well-being is not a priority, there is no better time than now for us to take our lives into our own hands. As Jalil Muntaqim has urged: we must be our own liberators! A pathway toward that liberation involves creating spaces by which we, New Afrikans, can first relate to one another, provide for one another, and then take those relationships and that work into the broader world and start to impact and direct every facet of our daily lives. With most of our historically Black neighborhoods decimated, and the majority of our time spent working to survive, there’s little room and time for us to pour into ourselves. Thus, we have to take advantage of what does exist. These football programs offer Black Bayarians a real opportunity for development; perhaps organizers here claiming to be about Black liberation will find areas for support and partnership and help players, coaches, and families deepen the work they’ve long done to have a positive impact on our people

Authors Note: I wrote this piece a few days after we did the video and photoshoot for the gloves. Since that shoot and the writing of this piece, the Bay Area football community lost a legend and pillar, Coach John Beam. I myself never got the chance to play for Coach Beam, but I am still a by-product of the infrastructure and opportunities he gave to student-athletes over the course of his multi-decade career. I remember those passing leagues at Laney on Tuesday and Thursday nights when I was in high school. That’s a space where I and so many of my peers got the chances to not only compete and refine our skills, but be in community amongst so many amazing players and coaches across the Bay. And that doesn’t happen without Coach Beam making his field and facilities open to us. This piece and the work of People’s Programs with student-athletes is of that ethos of Coach Beam. May we honor his life and legacy by carrying the torch of creating opportunities for others to grow and succeed!